It turns out the answer to my question "Laurie Olin vs. Dave Hickey: What Makes Them Different and What Does It Mean" is in a Hickey essay called "The Delicacy of Rock and Roll" (which is also the first essay of his that I ever read, the one made me go searching for more). It's about two short films he saw in grad school; one by Stan Brakhage ("that might be characterized thematically as 'very nervous' and sort of about 'film itself' [with] a great deal of panning, swooping, jiggling,dipping and zooming"), the other Andy Warhol's Haircut No 3, a film that is nothing but a very close shot of a man's hair being cut, for a long time, and finally, the man lighting a cigarette.

"Brakhage's practice...was essentially tragic. His films strove toward a condition of freedom and autonomy, fully aware that the work itself, for all its abstract materiality, could never free itself from cultural expectations. Nor could the artist, for all the aleatory and improvisatory privileges he granted himself, free his practice from the traditions of picture-making...Brakhage told us what we already knew as children of the Cold War, that no matter how hard we tried, we could not be free. Warhol's film, on the other hand, told us what we needed to know, that, no matter how hard we tried, we could not be ordered--that insofar as we were tiny, raggedy, damaged and disorganized human beings, we probably were free, in some small degree, whether we liked it or not...Warhol's self-inhibiting strategies liberated him as an artist and liberated his beholders, as well, into an essentially comic universe."

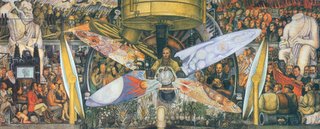

Tragic vs. comic. Olin: with his visceral understanding of how his predecessors, English designers in the 18th century, brought to bear all their skills and knowledge to create some small plot of beauty and order against the passage of time, decay, ruin, death, etc. And Hickey: with his faith in rock and roll (the Stones again!) as a metaphor for democracy and in popular/commercial culture in general as the source for all truly pleasureable/meaningful high art, who never really mentions the passage of time, decay, ruin, death, etc. at all, but is very interested in democracy--how people are living, talking to each other, getting by.

I was thinking of tragic vs. comic in relation to the Warner Herzog movie I saw tonight, Fitzcarraldo (at the Brattle, which continues its fundraising in hopes of staying open). Herzog flirts with Issues (the echoes of colonialism and the Heart of Darkness, the power dynamic in cross-cultural encounters, the exploitation of indigenous people by outsiders--anthopologists, filmmakers, or otherwise) but in the end the movie is pure fantasy, skipping by tragedy to stage operas on steamships. I'm not sure I've ever seen a movie that asks for such suspension of disbelief. At one point, our projectionist actually showed a 10-minute scene out of sequence, a full hour before it was supposed to appear. No one noticed until we saw the same scene the second time, in its proper place; the first time around, it had seemed like just another disjointed, fantastic lurch forward in an essentially comic universe.

A couple of posts back I mentioned that Public Space Project is helping to install a temporary exhibit in the lobby of our building. For the last 4-5 days, we've been scavanging junk. Last Friday, just a stone's throw from Outflow #70, we visited the

A couple of posts back I mentioned that Public Space Project is helping to install a temporary exhibit in the lobby of our building. For the last 4-5 days, we've been scavanging junk. Last Friday, just a stone's throw from Outflow #70, we visited the