eating, drinking, overthinking

That's the title of a self-help book I saw in the bookstore window today, but it would make a good name for my blog, too. Another one would be: "Hey, Look At Me! Look At Me!"

One of the things I miss about Mexico City is the crowds and the activity of people on the street. A few blocks away from the Zocalo, vendors line both sides of the streets for blocks on end. The busiest intersection sounded like the trading floor on Wall Street--hundreds of voices rising and falling, shouting out the names of products and prices.

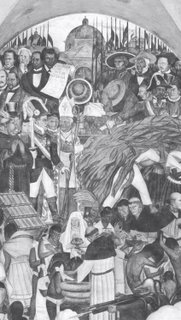

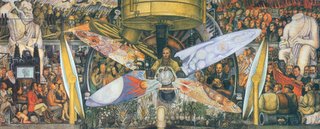

You can see this experience of urban density reflected in Mexican murals, which are as crowded as the busiest city plaza or rush-hour subway car. We saw a half-dozen of Diego Rivera's murals from the 1930s, including Man at the Crossroads (above, and detail below left) and History of Mexico, both of which are every bit as monumental as their titles suggest. Rivera and his contemporaries Jose Clemente Orozco and David Alfaro Siqueiros were classically trained, and they enlist traditional compositional strategies (e.g. diagonals draw your eye toward key elements in the center that command attention, etc.) But your first impression of one of these murals is of a wild abundance, bursting at the seams in all directions at once.

There's a John Ashbery line I'm just remembering, in which a character is vomiting out images and run-on associations. These murals feel the same way, joyously. Bhgleah: out comes upscale dinner parties, workers' strikes, microbes, Darwin, police crackdowns, Lenin. As with Ashbery and his fellow New York School of Poets, there's a feeling in Rivera's murals that anything could materialize at any time, and all juxtapositions are possible.

There's a John Ashbery line I'm just remembering, in which a character is vomiting out images and run-on associations. These murals feel the same way, joyously. Bhgleah: out comes upscale dinner parties, workers' strikes, microbes, Darwin, police crackdowns, Lenin. As with Ashbery and his fellow New York School of Poets, there's a feeling in Rivera's murals that anything could materialize at any time, and all juxtapositions are possible.

The official narrative of History of Mexico runs right to left, from scenes of an idealized pre-Columbian past, to the Spanish conquest of Mexico, to the Mexico of the 1930s. But a linear storyline is not what you experience as you actually look at the mural. Your eye drifts back and forth, there's equal attention to detail seemingly everywhere you glance, and action rewarding each new field of focus--as if, say, you were overlooking a vendor-lined intersection on a busy street.

Rivera and company meant for their murals to be public works. Here's a line from Siqueiros' manifesto from the early 1920s:

"We repudiate so-called easel painting and every kind of art favored by ultra-intellectual circles, because it is aristocratic, and we praise monumental art in all its forms, because it is a public property...art must no longer be the expression of individual satisfaction which it is today, but should aim to become a fighting, educative art for all."

I'm only just starting to read Desmond Rochfort's Mexican Muralists about the origins of this movement from Mexico's political upheaval at the time. I can't think of an American art movement to compare to Rivera's group, who believed that they were helping to express and shape Mexico's national identity. For their brand of self-consciously revolutionary rhetoric, it seems like you'd have to go back to Adams and Jefferson. (Interestingly, Rochfort digs up a letter from an American artists in the 1930s writing to FDR about Rivera and asking the U.S. government to support similar works at home.) At the same time, while they were calling for a uniquely Mexican art form, Rivera, Orozco, and Siquieres all studied art in Europe--Rivera lived abroad for 14 years--and were excited and influenced by Cubism and Futurism.

Anyway, enough book report. Time for bed.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home